Lucas vanBinsbergen ’27

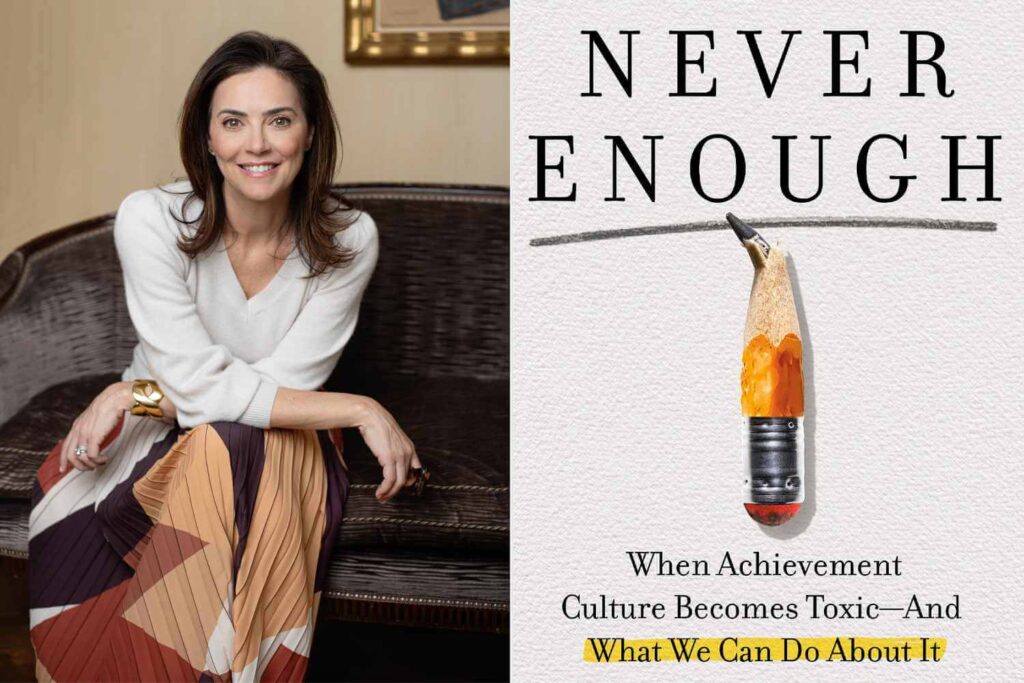

On Thursday, April 11, a webinar for EA parents was hosted with Jennifer Wallace, The New York Times best-selling and award-winning author of Never Enough: When Achievement Culture Becomes Toxic and What We Can Do About It. Wallace’s book discusses the idea of toxic achievement culture and the concept of students being unsatisfied with their academic and/or athletic results due to external pressures. She also highlights the fine line between toxic and non-toxic achievement culture, utilizing students’ personal stories to align with this idea of a toxic achievement culture.

Head of Upper School Michael Letts discusses the purpose of this webinar, “A lot of us have read Never Enough by Jennifer Wallace, and I think it speaks to our concerns, not only as teachers but as parents, about the pressures that you are under and how we as teachers and as parents can help you navigate those. I think it’s an important discussion that I think recently, certainly post-COVID become much more of a concern.”

In an interview with Greater Good Magazine, Wallace discusses not only how students felt about experiencing toxic achievement culture but also how parents were dealing with it as well. She surveyed 6,500 parents and discovered that 87% felt strongly or somewhat strongly that they wished their child’s lives were less stressful and 75% percent felt strongly or somewhat strongly that they were responsible for their child’s success in life.

This raises the topic of “living through” one’s children. Wallace discusses that, for years, psychologists have been directing parents on how they can help their kids, while they should rather be focusing on helping the parents develop more of a sense of resilience so that the child can have a strong sense of support. She explains, “To help the child, first help the caregiver.”

Wallace’s studies, according to the Greater Good Magazine interview, suggest that the toxic achievement culture one experiences can also be based on socioeconomic standing.

Wallace mentions that “at risk,” under-resourced children primarily deal with problems involving poverty and community violence. On the other hand, there has been a recent rise in toxic achievement culture on the wealthier side, specifically in the top 20% and 25% of household incomes that earn $130,000 or more annually. Wallace found that “a disproportionately high number of these students are experiencing negative health outcomes, like anxiety, depression, and substance use disorders, compared to their middle-class peers.”

Caroline Graham, Upper School counselor, gives her opinions on toxic achievement culture and its impact. She states, “I think that toxic achievement culture can result in perfectionism. It can also lead to really rigid all-or-nothing thinking, and when individuals have all-or-nothing thinking or perfectionist thinking, it’s really this notion of not necessarily that I have to be perfect, but it’s this idea that I am not good enough…achievement doesn’t get to define self-worth.”

Due to the highly competitive environment at Episcopal, it is to be hyper-fixated on grades, but it is important to find value in other forms of achievement. Elizabeth Hershey ‘25 comments, “The academic environment at EA is definitely competitive because we are such an elite school, and it is easy to fall into the “grade-seeking” mindset. I think the best way to combat this thinking is by pinpointing other moments of pride and recognizing the benefits of them. For example, rather than gaining self-assurance from a good grade, I find self-worth when I share my opinions in class or give a compliment to someone I wouldn’t normally talk to. If you place value on other aspects of your life, and not just your academics, the pressure to get good grades won’t be as strong.”

Graham also notes that it is unwise to discard achievement culture fully but rather to recognize the difference and understand what to do to fight against its toxic side. She explains, “It’s okay to be success-oriented, and I think that that is also a really important and fundamental thing to sort of learn about yourself. But, it starts to become toxic when it is wrapped up in comparing yourself to others and competition and then also if your achievements and success are tied to your self-worth.”

From his experience as a student, Luke Miller ’24 comments on toxic achievement culture, saying, “Toxic achievement culture is something that I can see all around me, whether that be in school or sports. I feel that to combat this, we should aim to build each other up rather than break each other down. At the end of the day, we are all part of one team looking to better ourselves and the world.”

TOXIC ACHIEVEMENT CULTURE: Wallace’s book uses students’ stories to demonstrate when achievement culture goes too far and how we can fix it.

Photo courtesy of people.com