Alex Gobran ’23 | Nayan Shankaran ’24 | Rohan Dalal ’25

After more than a decade of development, The College Board has been piloting the new AP African American Studies course across 60 schools in the United States during the 2022-2023 academic year. Although the course will be available to all high schools starting in the 2024-2025 academic year, EA has no current plans to adopt the course for next year.

The units of AP African American Studies are 1) origins of the African diaspora; 2) freedom, enslavement, and resistance; 3) the practice of freedom; and 4) movements and debates. Chair of the History Department Steven Schuh explains that EA’s existing history courses touch on some of these units. He states, “Not to the depth that [AP African American Studies] will, but your U.S. History class covers many of those topics.” Regarding the other ways that EA educates students about African American history, Schuh adds, “We discuss many African American authors and contributions, given that particularly the AP framework is a little bit stringent. But, I think we do a good job.”

Among the existing EA courses, the curriculum of AP African American Studies has the most overlap with Honors Identity and Culture in Modern U.S. History, which is a course for seniors taught by history teacher Jerome Bailey. Schuh believes that the second, third, and fourth units of AP African American Studies are explored in Honors Identity and Culture but that there is not much discussion of the origins of the African diaspora.

Bailey also thinks that he incorporates similar material to that of the AP African American Studies course, elaborating, “Particularly the movements and debates…We spend a lot of time on those units, especially Reconstruction in the beginning of the year, and then also looking at how the Civil Rights Movement and then the present day Black Lives Matter movement have also been impacted by previous generations as well.” Bailey discusses the Jim Crow Era, the Civil Rights Movement, the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, and the Black Panther Party to advance his discussion on the political activism and involvement of African Americans.

Bailey reveals that he hopes to teach AP African American Studies at EA when the course is available to all schools, due to the course’s similarities with Honors Identity and Culture. “This course that the AP is working its way through will certainly give a deeper and broader investigation into the African American legacy in America. If it’s an elective, you may not get the same amount of attention… I feel like our school probably would get more students if it’s AP.”

English teacher Tony Herman believes that diverse perspectives should be integrated into EA’s curricula with or without the incorporation of AP African American Studies. “Do I think that in your EA curriculum you need to have read Black authors before graduating from EA? Absolutely. Do I think that we need to prescribe an AP course to EA students and say that that is a mandated part of the curriculum? I don’t think so,” he remarks.

Dylan Unruh ’24, who conducted a Lilley Independent Study on the Harlem Renaissance this academic year, agrees with Herman that although “African American studies is an important topic,” there does not necessarily have to be a specific course dedicated to that one topic, rather than the topic being intertwined with other history courses. He continues, “I think African American studies would be more beneficial as a part of APUSH. However, if it’s something that follows through, I think Episcopal should be in the lead of it.”

Bailey and Schuh are currently having discussions with the Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion (DEI) Office regarding the incorporation of diverse perspectives in history courses. Erica Snowden, the Executive Director of the Office of DEI, believes that such discussions are only a starting point for accomplishing this goal. She says, “At the end of the day, you’re trying to rewrite years of history that have been written by the people in power. And so, I think righting that wrong is going to take a long time.”

Snowden asserts that the history curriculum must be changed for students of all ages in order for diverse perspectives to be integrated into history. She specifically remembers hearing “in 1492, Columbus sailed the ocean blue,” but she now questions, “How can you discover something if there are people already there? And, how do we start talking about indigenous people like the Lenape who still live and exist on this land that our school is on? How do we talk about them from the very beginning and tell a true story and a true narrative?” Thus, she believes that “we have to redo the entire thing.”

Director of Diversity and Inclusion Ayinde Tate concurs with Snowden, stating, “Understanding the points of view of everyone, rather than the people who have essentially ‘won,’ would be way more beneficial to anyone trying to learn the true history of things.”

DEI Student Council Representative Chelsea Swei ’23 also believes that diverse perspectives should be represented in the curriculum, especially because students’ classroom learning experiences are intended to equip them with skills necessary for after high school. She reflects, “Exposing students to different cultures and experiences prepares them for life after high school. We are all eventually going to leave our small high school bubbles and enter the larger society. It prepares students to be educated and informed when interacting with people from all walks of life.”

Tate also stresses that other voices in addition to African Americans need to be heard. “Things are not simply black and white. And, there’s so much gray in the middle that we do need to actually speak about and learn about… It just allows us to have those different perspectives and allows the individuals to come up with what they think is the true path of history,” he explains. Swei also emphasizes the importance of pluralism in the classroom, noting that “it gives students the opportunity to learn more about cultures they rarely learned about. For instance, learning about Asian history during AP World History inspired me to minor in Asian Studies in college.”

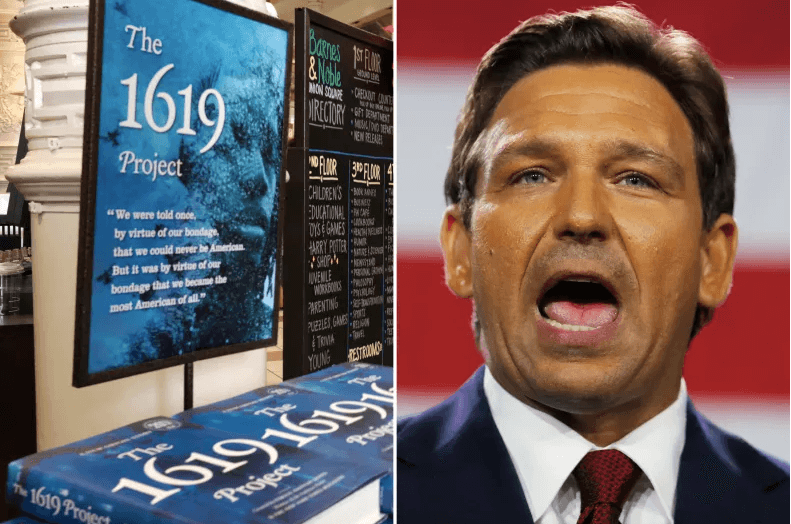

Despite EA’s optimism toward AP African American Studies, Florida Governor Ron DeSantis (R) has recently banned the course in all Florida schools, calling it ‘indoctrination.’ In response, “The College Board purged the names of many Black writers and scholars associated with critical race theory, the queer experience, and Black feminism. It ushered out some politically fraught topics, like Black Lives Matter, from the formal curriculum. And it added something new: ‘Black conservatism’ is now offered as an idea for a research project,” according to The New York Times.

In spite of this ban, Schuh “[doesn’t] see any impediment to us offering the course.”

Herman disagrees with the ban and DeSantis’ claim that the course is ‘indoctrination,’ remarking that AP African American Studies presents “a collection of a wide variety of African American voices that allows you to see their impact on American culture.”

Like Herman, Mengistie Hailemariam ’23, a student in Bailey’s Honors Identity and Culture course, thinks that critics of the AP African American Studies curriculum are not considering diverse points of view. He says, “AP African American Studies has been receiving criticism because people simply brush it off as ‘woke.’ In reality, it’s important to consider other perspectives.”

Unruh disagrees with DeSantis’ claim as well, stating, “I don’t think I would consider AP African American Studies to be indoctrination, but I’d have to look at the curriculum more to fully create an opinion on that.” Unruh acknowledges that AP African American Studies is “a course that needs to be treated with a high level of care” and that “courses like Critical Theory aren’t courses meant for young middle schoolers,” but he asserts, “Banning them from school definitely sets a dangerous precedent.”

Photo courtesy of News Week

In general, Herman believes, “The goal is to break free from the change, look at some tough stuff, read some tough stuff, and try to figure out how we can be better people because of it.” He thinks that by using this approach, we “get raised into a level of consciousness that allows us to move in our spheres within knowledge of what has happened and what is still happening and how we can be proponents of change in a positive way.”

Even though some topics were omitted from the AP curriculum, Bailey wants to discuss those topics when he teaches his own African American studies course. “I was upset by the omissions because I think that’s important history that needs to be covered. And so, I would definitely find ways to include that in the curriculum if the class was AP or not,” he asserts. He specifically mentions that he will teach about the history of the Black Lives Matter movement, which is occurring in the present day.

In particular, Tate believes that the exclusion of Kimberlé Crenshaw’s work surrounding intersectionality diminishes the power of the revised curriculum. “There are so many works in writing and input and influence that feminist writers have produced and contributed to African American history on the whole. There’s not really a full scope as to what they’re perceiving as queer theory,” he says.Ultimately, Unruh believes that students as well as teachers have a responsibility to be attuned to and analyze a diversity of perspectives. He concludes, “I think students have the role of bringing their own perspectives to school. It’s the teacher’s job to provide a wide range of perspectives, and it’s the student’s role to come into each class open-minded and ready to listen and ready to sometimes disagree with other students or sometimes disagree with their own opinions.”