Noble Brigham ‘20

Photo courtesy of Noble Brigham

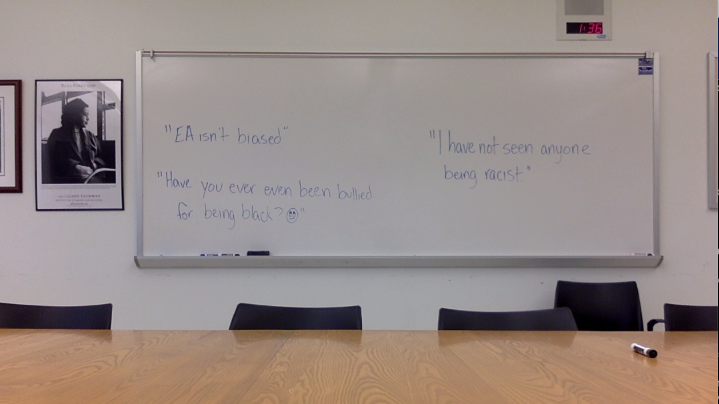

Students and faculty were shocked and upset by a recent incident where a student posted an image many considered racist on social media, sparking outrage. This has resulted in the student’s departure from Episcopal but has also created reckoning and conversations in the community. Some felt it was an overreaction and others felt the then-student was fairly disciplined. However, this episode was far from a “one-off.” Episcopal has a long and tangled racial history.

During a Can Drive chapel skit in October, 2012, a student dressed up as “Canye” West by putting a printout of West’s face over his face. Some saw this as a form of blackface and the Vestry publicly apologized.

At the time Courtney Portlock, then Director of Diversity and Inclusion, said, “Hopefully, moving on from this point, folks will just be mindful and know that there are some consequences attached to resembling blackface.”

Sam Willis, then Upper School Diversity Coordinator, recounted, “When the student entered the chapel there was a senior who audibly reacted to the sight of a student wearing someone else’s face and that student called it out as a form of blackface.”

“Generally the EA experience is one of privilege unless you’re a minority. You feel ostracized because you’re a person of color …There’s no caring about the black student or the black student’s experience,” said Jacob Lowe ‘13, now in the corporate world working for AT&T in Oklahoma.

He does not feel EA suffers from institutional racism, but of the skit he recalled, “The thing that shocked me the most was it didn’t seem like anyone cared …EA’s response to it was very bland. It felt very carpeted, like they’re trying to be extremely defensive.” He continued, “Good corporations and businesses like EA have a tendency to treat things as isolated incidents when they are actually not.”

An anonymous EA parent stated, ”The Episcopal Academy took away my son’s First Amendment rights by not allowing him to use the [N] word!” (they spelled it out) in a Philadelphia Magazine article from 2015 titled “Racial Profiling on the Main Line.”

In November, 2013, another EA parent was arrested by the Newtown Township Police Department for shouting the N-word in an altercation with a Malvern Prep football player after Malvern beat Episcopal 49-21 and the parent’s son and Malvern player had argued.

At the time, Episcopal officials said, “Clearly, there is no place for this type of hateful speech and behavior at the Episcopal Academy, and this parent will not be permitted on campus for the upcoming EA-Haverford-AIS weekend.”

This was echoed by T.J. Locke, the Greville Haslam Head of School, in a September email: “Intolerant language is a violation of what we stand for at The Episcopal Academy. We are rooted in our faith and in our Stripes, and we strive to create an inclusive community.”

For most of Episcopal’s 234 years, though, black students were never admitted. Tom Dalzell ‘69 explained in a recent interview, “We thought that having two Catholic guys coming into the class was diversity.”

The first African American students were admitted around 1966-67, and the first to graduate was Darrel Francis ‘71. The first black lifer to graduate was Paul Hayward ‘83. These dates are in line with other Inter-Ac schools, but the Friends schools were leaders in the struggle for integration. Germantown Friends, for instance, admitted black students in 1948.

Over the years, there has been much improvement. Since the 1990s, EA has had a Director of Diversity and Inclusion. The school now has 28% diversity, a number that continues to improve.

Ellen Hay, Director of Admission from 1986-2011 said, “It was very important to me to have students of color.” Hay increased outreach to families from different racial and socioeconomic backgrounds and also worked to achieve gender parity.

Still, 39.5% of students in a September survey with 311 responses believed EA does not do enough to combat racism among students.

In a 2014 interview with Scholium, Portlock said that after Hayward and Francis had spoken in a chapel around 2007, “[what] was particularly compelling was that things haven’t really changed that much. And actually, in some ways, they thought things were better when they were students.”

In that article, Francis said that he valued his EA education, but remembered, “Not everyone in the community was excited about us being there. One of the big things back then was that they absolutely refused to drop any academic standard to allow us to attend. And that became an issue coming from my public school in North Philly. It was a shock to say the least. In my case, I had to repeat freshman year.”

Hayward told Scholium: “From my more recent visits to campus I think you guys have more racial tension than we did. It was really interesting for me to see how a school takes steps backwards.”

Society has been wrestling with its complex racial history too. In the past year, evidence has emerged that Ralph Northam, Governor of Virginia and Mark Herring, Attorney General of Virginia, wore blackface at parties. More recently, photos surfaced of Justin Trudeau, Prime Minister of Canada, dressed as Aladdin with brownface at an Arabian costume party held when he was a schoolteacher in 2001. Herring and Northam have held on to their positions despite calls to resign and national media attention, but Trudeau is up for re-election on October 21st.

Many feel that the conversation is ongoing. Willis said, “We continue to think about issues of diversity and trying to make this the most inclusive environment. I think we still have some ways to go, but we’re aware of that and I think that that’s something that we’re trying to be proactive about as opposed to being reactive.”