Aarushi Singh ‘20

This year, Episcopal offers two new science courses outside of the conventional biology, chemistry, and physics students are required to take. Cognitive Neuroscience and Principles of Engineering have made their debut as semester-long additions to the four previous science electives at EA. The two courses, each worth one-half of a science credit, will run during the fall and spring semesters.

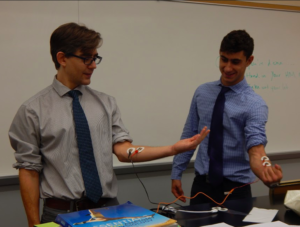

Photo courtesy of Elizabeth Palumbo ’19.

Cognitive Neuroscience focuses on “[linking] the biology of the brain to the cognitive psychological processes that allow us to think and learn,” according to the Upper School Program of Studies. The course is taught by Upper School Science Teacher Matthew Shapiro, who got the idea for the course about a year ago, after teaching similar classes at other schools. “I have a Master’s degree called ‘Mind, Brain, Education,’ a degree that tries to unite neuroscience, cognitive science, and education,” says Shapiro. “Mrs. Limaye, the head of the Center for Teaching and Learning, asked me to do a presentation about my degree in the classroom… I thought, this could be cool—maybe I could teach this to students.”

Concepts studied in the course include sensation perception, learning and memory, social cognition, and consciousness. “My big takeaway for students is to have a better understanding of how their brains are constructing their realities,” Shapiro says. “We have these brains that are doing things for us all the time, but we don’t stop and understand what they’re actually doing.” Shapiro also hopes to incorporate the science behind studying and learning into the course as well.

The curriculum contains labs and activities designed to give students a better understanding of the scientific topics studied in class. “We did a lab where the students hooked up a bunch of different muscles and neurons to some electrophysiology,” says Shapiro. “They could see the brains talking and see their muscles spiking, or having action-potentials.” Mickey Rymal ‘20, a student currently enrolled in the course, says “Some high school labs get boring. But we literally hooked up electrodes to each other. Mr. Shapiro put an electrode on his hand. When Ellum flexed, his hand would twitch. That was probably the coolest experiment we did.”

Students also examine a different case study each unit. “The first unit, we did the case of a really fascinating neuroscience patient named H.M. who had his hippocampi removed, and interesting things happened,” says Shapiro. “We have another case coming up about someone who had split-brain surgery where they actually split the right and the left hemisphere.” At the end of the term, students will design and conduct their own experiments using the concepts they learned.

The course has garnered positive reception among students. Ainsley Shin ‘20, says “[The class] is really interesting. Mr Shapiro is super interested in the course, so that makes us more willing to actually learn.” Rymal says, “It’s really interesting material… I never thought my school would teach it; it’s more like a college course than it is a regular high school course.” Shapiro shares his students’ enthusiasm for the class, stating “I’m really excited… It’s just fun to be able to go into the classroom every day to talk about the brain, and hopefully get other people enthused about it like I am.”

Principles of Engineering, taught by George Lorenson, Chair of the Upper School Science Department, centers on engineering design and application as well as the work of an engineer. “The goal of the course is to give students the ability to experience what an engineer would do in the field,” says Lorenson. “It hopefully gives them exposure to the four main types of engineering: mechanical, civil, chemical, and electrical.” Lorenson hopes to provide students considering engineering as a career path with an understanding of what the profession entails. Lorenson states, “A lot of people say ‘yeah, I want to be an engineer,’ but they don’t necessarily know what that means… Hopefully, [the course will] expose them to the engineering design process, so they understand what it means to be an engineer.”

The curriculum allows the students to employ principles from class in real-world applications. “We’ll do some bridge-building, which is kind of a combination between mechanical and civil,” says Lorenson. “For electrical, hopefully, we’ll look at some regenerative braking in rail cars for passenger trains—I’m not positive on that one, though.” Jake Landaiche ‘19 says, “My favorite thing we have done so far was to determine the course of action for a hypothetical oil spill based on data we gathered from an oil cleanup lab.”

Lorenson has extensive firsthand experience in the profession. “I was an engineer before I became a teacher,” said Lorenson, “so I have fifteen years, roughly, of field experience in engineering before I made the switch to become a chemistry teacher.” He hopes to use this experience to convey an understanding of the profession to his students. “I want them to understand what an engineer does, the level of difficulty of the work, and hopefully the reward of the work as well. I want them to appreciate that it’s a little beyond just ‘build something and tear it apart’—there’s a lot of math involved, a lot of design involved, and a lot of creative thinking.”

Principles of Engineering and Cognitive Neuroscience allow interested students to pursue scientific interests not otherwise covered by the required Upper School science curriculum. Along with other unconventional courses such as Astronomy, Oceanography, and Scientific Reasoning, they expand the diversity of the science program at Episcopal.